You have described yourself as a bit of a “carefree” kid growing up – daydreaming and drawing, getting into trouble, getting kicked out of school, etc. How did you become interested in drawing? Were you into comics as a kid, or just interested in self-expression?

LU MING: I think that a love for painting is a gift, and I think it’s not a talent for painting, but rather the love for painting that is the real gift. Painting is life itself for me. It’s the thing I need the most, and the most beautiful thing within my life. Of all my memories, the first thing I can remember doing is painting. Maybe this is why I’ve never cared much about other things, such as eating or sleeping or working for others to make money. I’ve always only really cared about painting. If there were other things I could have in my life, things or experiences, of course I would be happy, but ultimately, they don’t matter to me, it would make no difference to me. All I need is a brush and light. As far as comics go, it actually wasn’t until high school that I started creating them. I love painting, telling stories, or just as you put it, expressing myself. Creating comics satisfies all of these needs that I have. To me it is the perfect task.

At what point did you decide you wanted to study art and make a career of it?

LU MING: I started seriously and systematically studying fine art at age seven, and all the way up until now I have never stopped practicing every day. I’m not sure whether I’ve turned into an “artist”, I am just doing the thing I love the most. Becoming a comic book artist as a profession began during my high school days. I wished to become a comic book artist because the feedback from my readers made me feel a sense of identity and made me feel that I was not alone. This feeling you get from that feedback is much better than the money spent to buy another Play station!

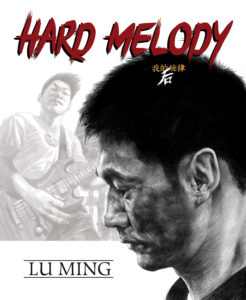

Your earlier comics appeared in Chinese fanzines, including “Mélodie d’enfer”. Was this an earlier version of HARD MELODY, or a separate story coincidentally named “Mélodie”? Were there many differences between “Mélodie d’enfer” from 2001 and HARD MELODY in 2013?

LU MING: In fact, HARD MELODY is the “mental sequel” of Mélodie d’enfer. But it is still a relatively independent story. When I made Mélodie d’enfer, I was 16 years old, I already felt I had a lot of insight into the world and about life, so I put the three souls in a hypothetical extreme environment and created a story about searching for the “meaning of existence”. I think this is a primary confusion and concern for many young people. And as it turned out this story was loved by many people my age.

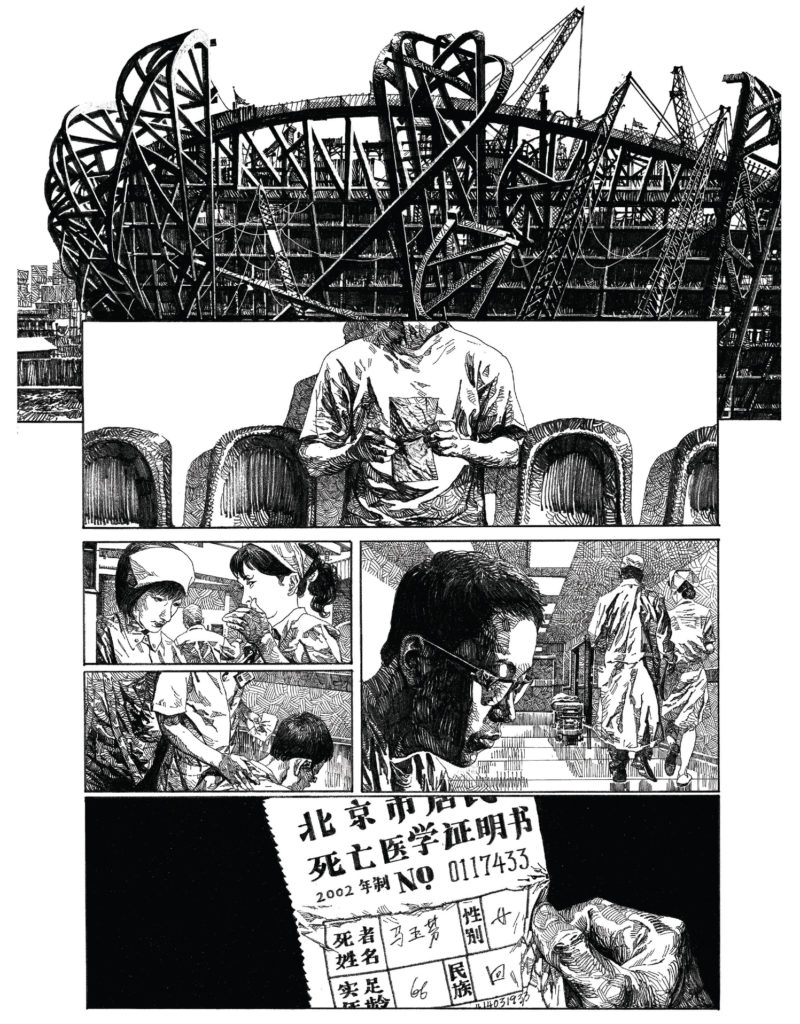

Many years later, some readers from that time left me messages on Chinese social media, hoping that I would create a sequel to Mélodie d’enfer. I was surprised at the time because I’d never really thought about it. But then immediately I started to think and imagine: if the story of Mélodie d’enfer really were to have a follow-up, then the characters in the story from that year—the three souls would have now been reincarnated and would be 30 years old like me. At thirty, what would their lives look like? Facing this new country, this fast-moving society, facing the notion of working hard to make money for and from other people, actively or passively forming families, to face the road that lay ahead of them that sometimes needs to be considered, and the blue skies that can only be embraced by keeping their heads up, what choices must be made; what kind of people would they have become? I wanted to know, too. So, with this in mind, I started to create HARD MELODY. Unlike Mélodie d’enfer’s teenage fever dream, HARD MELODY is more like a faithful and mature account of this idea. I summarized the living conditions of young Chinese people my age that I know into three modes: succumbing to “life” / playing with “life” / being loyal to oneself, and how “life” can interfere with it. It is a fight to the end. These three states of living have become the different story lines of the three protagonists of the story in HARD MELODY.

This time I didn’t want to make any evaluations or judgments about it, just an honest record. This is the truth as I see it.

You have done a lot of work in cinema, most notably with the legendary Tsui Hark. How did you first meet him? What is your relationship with him outside of those projects?

LU MING: The first time I met with Director Tsui Hark, it was because he wanted to find a good comic artist to draw some of his “B side” original stories into comics and publish them, because he felt that those stories might not be suitable for making into movies, and he thought I was the best comic artist in China. This was back when I was still in college. But I turned down his requests at the time because I would only spend time working on my own stories. But then I was invited to watch the uncut screening of the movie “Seven Swords” that he hadn’t yet finished filming at the time. I loved that movie so much! So, at that point I agreed to create a short comic of only a few pages for that movie, as long as I could write the story myself. Later down the line we became friends. When he started to make a new movie a few years later, he asked me to design the plot of an entire section of the story—using my comic artists perspective. Then I also drew a lot of cutting concept designs in movies, including that portion. That experience made me fall in love with the film making process. After that, I did the same for four or five of his other movies.

HARD MELODY has a very “Hong Kong Noir” feel to it, like the kind of stories you would see in films by directors like Wong Kar-wai and Johnny To. Are you attracted to those kinds of cinematic dramas full of themes like brotherly sacrifice, etc?

LU MING: No, I don’t really like Hong Kong noir movies. I don’t believe it has affected my work, I would do anything for my brothers, my friends, and the people that I love, and I think this is the “brotherly sacrifice” theme that just naturally shines through in my work. I have also seen what the real “Mafia” looks like in real life. Compared to the real situation, Hong Kong film noir movies are simply cartoons.

What kind of movies do you like? Do you prefer contemporary stories or historical fantasies?

LU MING: I like the kind of movies that originate from the real, genuine, and strong emotions of the creators. They cover a topic that the creator really wants to talk about from their heart. The source of this desire to confide in the audience and to be able to fully express it is like grabbing a handful of sand from the beach and using 90 minutes for each grain to drain from that hand, leaving behind tiny specks of gold, reflecting with the brilliance of the shining sun. To me I have no preference between modern stories or historical and fantasy stories. My favorite director right now is Clint Eastwood. I like his two recent films.

You are also very committed to your music, as Guitarist for your band NUBEER. Essayist Walter Pater said in 1877 that “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music” – which medium do you feel better expresses yourself: your art or your music?

LU MING: I think everyone who paints also needs music! Although they are both art, I believe painting affects you more directly in the soul, and music often affects your body first. Human muscles and blood flow will have a direct reactionary effect from music. If you only sit and paint in your house, you will become an otaku and that would be such a shame and a waste! Therefore, the painter needs to paint for a while, then go out and hook up some effects pedals and speakers onstage for a night, and then blast out to ride a motorcycle to another place and see other worlds, and after that, come back to paint.

At least this is how I am. Otherwise, what would I have to draw?

Who are your favorite musicians? Do you listen to music while you draw/paint? If so, who inspires your visual art?

LU MING: BEETHOVEN!!!!!!!!! I have always listened to music while I paint. In fact, I have been listening to tons of music forever, ever since I got a walk man in high school, primarily dramatic music: classical and metal. I think Beethoven’s best friends would be Dimebag Darrell and Eddie van Halen if they all were still around. I also listen to many kinds of good music, Mongolian or Tuvan folk songs, blues that isn’t super old or traditional, jazz, hard rock, post rock, new age Japanese music, etc. But now I don’t really listen to songs while I paint, because I’ve found that my emotions will be steered by the music and become the emotions that the music wants to make me feel, which is not what I want. Now when I draw, I put on some “white noise” to have the presence of sound, but it has to be sound that doesn’t heavily affect my emotions, such as putting news on in the background.

Much of your work celebrates the past, particularly the various eastern cultures who have left lasting marks over the centuries. Much of your work, even the contemporary stuff, seems to be haunted by ghosts from the past. Is this intentional or do you think it is more of a subconscious influence from the amount of study you have done?

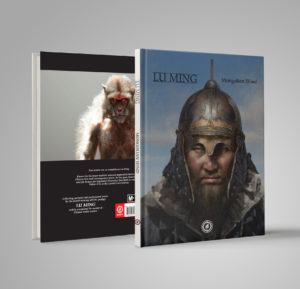

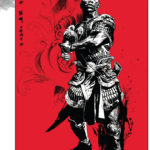

LU MING: Yes. I feel that I have sort of a compelling mission or duty. I feel that I have been given a responsibility to make sure people do not forget the past. Many of the works I painted, as well as some sculptures I’ve made, are all showing a kind of beauty that has died. I think North Asian armor from the 5th to 13th centuries is the most beautiful standard bearer and representation of this kind of beauty. It is both a source of pride and a sad fact: that armor is buried out in the yellow sands and has been gradually weathered down and forgotten, but in fact they are still hard; they used to shine, and today the warrior that lived and fought inside that armor is dead and gone.

It’s like Chinese characters, Japanese architecture, the yurts out on the grassland, the knives sitting in museums. These are beautiful and precious remains. Industrialized civilization and globalization make us wear the same T-shirts and watch the same porn hub clips, and we may eat the same artificial meat in the future, but heck, I’d like to say I prefer to remember the differences. These differences will become friends. I think I have a mission and duty to show them today, at least to the young people in China, how different and special we have been. The scope has expanded a little bit to cover the entire breadth of northeastern Asia, those countries, civilizations, those once proud, self-realized, and magnificent heroes, I saw and continue to see them now in their original forms. No matter who forgets, I will always remember, and then stubbornly remind people that they once existed!

Some of your work, most notably HARD MELODY, is a subtle commentary on postmillennium China, and how expectations and dreams have changed in recent decades. Do you feel there are strong or unique differences in China’s recent development versus other Western cultures? Is it easier or more difficult to be a consumer in China than, say, in France?

LU MING: I actually don’t like the modern China now, but for the opposite reason, I think it’s because we have become more like the Western world, and at the same time, the Western world has also begun to become like us. I am not very old, but I have been to many parts of the world. Even this kind of experience makes me feel that we have lost a lot of the truly beautiful qualities of the world outside of this focus on ideology. I really like this American drama series “Yellowstone”. I appreciate the Japanese attitude towards politics and their own culture. I absolutely hate and abhor any form of “domination”, especially the use of “economy” as handcuffs. When I was at Burning Man in 2018, I was sitting on the white sand of Play, away from the crowd, watching the deep blue mountains in the distance lying quietly under the pink sky caused by the afterglow of the setting sun, smelling the wind, listening to the time slowly flow by. I felt that in that moment I saw the world for what it truly is. The world I like to exist in. I’d trade all the time I’d spent in the world outside of the time spent painting for the feeling I had in that one moment.

What projects have you worked on since HARD MELODY? What projects are you working on now?

LU MING: Right after HARD MELODY was finished, I began to create new stories. I have so many stories still to tell. The new story I am currently working on is called “Lonely Arslen.” I started writing it in 2015. When I had a book signing for the readers in France, I drew the first frame of the story on the signature of each book. It took me five years to finish writing it, and now I have been painting it for nearly a year. This story describes loneliness. People always love to hear about the sunshine. People always say “Oh! This night will pass, but the dawn will come soon!” People love flowers because of their bright colors. But I suddenly thought: Is there not also dignity in darkness? Darkness is just being itself. If dawn never comes, shall we all commit suicide in the dark? Also, to speak to the notion of the shining sun, a mountain facing the sun is great, but why is the stone sitting on the shaded side humble? This story is about drawing an ordinary stone sitting in the shadows to prove its dignity and allow it to not feel sad or pitiful. Someone loves that stone. Anyone who has studied painting knows that the colors in the dark parts are the most saturated and vibrant.

Are there any “dream projects” you hope to create some day?

LU MING: Yes, I hope to paint the story of my grandfather, and another story about the war between Mongolia and China in the 13th century. I haven’t yet fully prepared all the research I need to compile for these stories. These stories, for at least fifteen years I’ve been engaged in all-round historical data research for preparation. I want it to be as if someone brought a camera back to 1234 and recorded every detail of the war. Warriors and heroes, taking off the armor of their respective camps and sides, are equally strong people. This is what I always believe, and I admire them all.